The importance of evidence-based design

Dr Dan Jenkins leads the human factors and research team at DCA Design International, working on a range of projects in domains including medical, transport, consumer goods and industrial products. Lisa Baker is a Chartered Ergonomist of the CIEHF and senior human factors researcher at DCA Design International. Here, in advance of an interactive workshop they will present at Design Council, they discuss the necessity of designing from a strong evidence base.

Design is rarely a solitary exercise. Despite perceptions brought about and perpetuated by celebrity designers, most products are developed by teams. The reason is that many products, like planes, trains or automobiles, are simply too complex to be designed by one person alone.

Even if they had the time, very few individuals have the required breadth and depth of skills, knowledge and attitude required to consider all aspects of the design. For products of any notable complexity, the idea that a single individual could fully research the product, it's context of use and commercial market, develop a concept, engineer it, test it, select materials and suppliers, and manage production transfer is simply a fantasy.

When it comes to working in teams, it's not enough to be confident in one’s own convictions. If the best designs are to be developed, it is imperative that each member of the team is able to explain the rationale for the decisions they make and convince others.

The most beautiful products, like works of art, elicit physiological responses: upon first sight, pupils dilate and heart rate quickens. The strongest brands can have the same impact. Users often place greater trust in these objects, they care for them and take time to use them effectively. But initial responses can also be fickle. How do we ensure that users not only remain engaged with products but can also use them to enhance system performance? Or simply put, how do we create beautiful things that also work beautifully?

Evidence-based design is a key component in developing better things.

Evidence-based design is a key component in developing better things. It's a philosophy that's critical for ensuring the team have a common objective and rationale for decision making when working in large multidisciplinary teams. Measurement is a critical part of this.

This kind of approach is something that a select few do intuitively. They create compelling arguments for a vision of the future and they have the authority or the gravitas to set a course that others follow. For most though, some form of systematic structure usually helps.

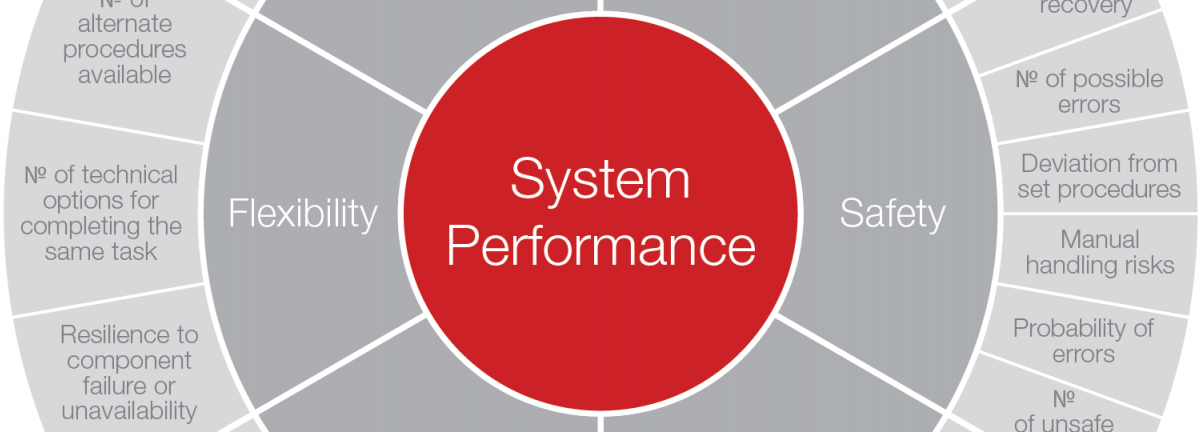

Fortunately, the human factors tool kit is jam-packed with methods and techniques ready to be used. These range from ethnography and contextual enquiry to more data driven approaches that are able to quantify aspects of system performance such as efficiency, effectiveness, resilience, intuitiveness, usability and inclusiveness. Furthermore, these approaches can also form the basis for ideation, providing inspiration and information for product improvements.

Ultimately a concise, well-supported argument for change is critical.

Ultimately a concise, well-supported argument for change is critical in ensuring that human factors are considered and communicated to a wide range of stakeholders. This may include those within the design team as well as end users, regulators, maintenance staff, sales and marketing, as well as those involved with construction and decommissioning. This way we can ensure that we are designing products and services that go beyond initial aesthetic appeal to enhance wider system performance.

Dan Jenkins and Lisa Baker will be presenting an interactive workshop on these ideas at the Ergonomic Design Awards on 22 September at the Design Council. The workshop will introduce a range of human factors tools and explain how they can be used to build, inform, and present a compelling business case for change that leads to better products and greater system performance.

A second workshop will also be presented which examines how designers can ensure inclusivity into later life, and how we design for physical issues of ageing and cognitive impairments such as dementia, for example.

Find out more about these workshops or, alternatively, please contact James Walton on 07736 893 347 or at j.walton@ergonomics.org.uk.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to keep up with the latest from the Design Council?