The secrets of the Chief Design Officer

This article is part of The Design Economy series.

An in-depth guide to the CDO phenomenon and the accession of design-thinking in the corporate world.

As Apple’s valuation shot higher and higher in recent years, a flurry of major corporations – Philips, PepsiCo, Hyundai – announced the appointments of Chief Design Officers to their boards.

This was no mere coincidence. Seeking to emulate the stellar success of design-led businesses like Apple, global companies are pouring investment into design. IBM, for one, announced a $100 million investment in its design capabilities last year, with the aim to hire 1,000 designers across its global workforce by 2018.

The twentieth century marketing perspective of ‘making people want things’ has transitioned to a twenty-first century approach of ‘making things people want’, and design – with its focus on users – is the route through which brands will either succeed or fail.

Demonstrating the importance of good design, the market-shaking exponential growth of young digital-based companies like Uber and Airbnb was fuelled by successful user experience and well-thought-out services that close the gap between provider and user.

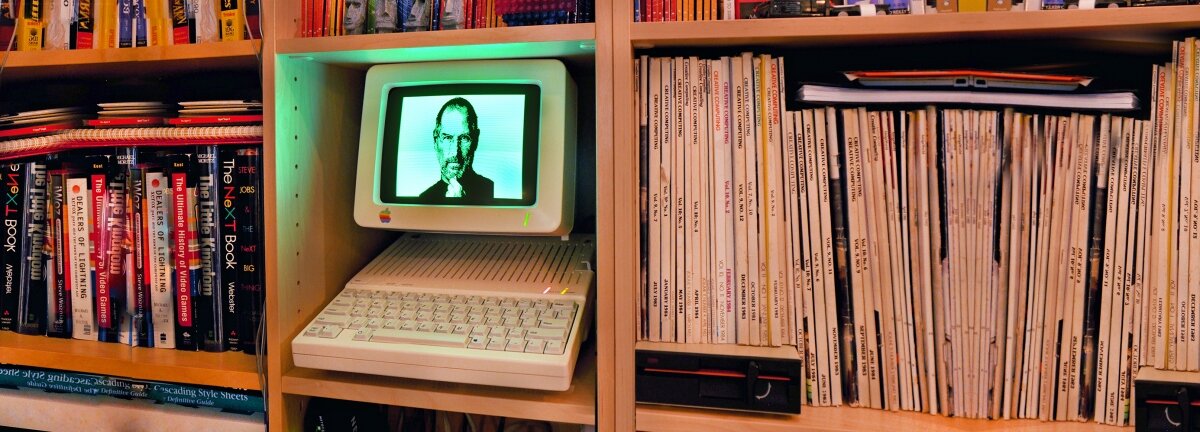

The question is: when it comes to corporations with established roots outside design, how is integrating design-thinking into business at the top best done? What qualities make for a great CDO: being a maverick creative genius or a Machiavellian business strategist, an outsider with a fresh and challenging perspective, or someone who can work in a friction-free way with the grain of the business? What does it take to do the job that Steve Jobs did? We look to leading CDOs and board-level creatives across a range of industries for the answers.

For Mat Hunter, Chief Design Officer of Design Council, the CDO’s magic lies in the ability to balance qualitative with quantitative factors, right-brain and left-brain functioning. Apple was exceptional, says Hunter, thanks to a culture created by Steve Jobs: “Even if the supply channels were stocked with a new product, even if everyone was thinking, ‘This thing is ready to ship,’ [Apple’s board] had the ability to step back and say, ‘But is it any good?’ ”

Leaders like Steve Jobs and Tim Cook have not just the sensitivity to recognise when design isn’t good enough, but also the power with which to write it off – even when killing the launch of a product can cost a business millions. Hunter says: “There’s something important in the board being able to embrace the qualitative and to act upon it, just because quantitative information is normally so much more powerful at board level.”

Having an individual who can straddle qualitative and quantitative thinking – and an organisation that will let them – is incredibly valuable. “Most organisations have people who are sensitive enough to work out that something’s not right, but they don’t necessarily have the power to oppose these things.”

The person who is sensitive, delicate and powerful at board level is quite rare.

Mat Hunter, Chief Design Officer, Design Council

The CDO’s understanding of a business as a whole – including finance, logistics and marketing, which have more quantitative approaches than design – is key to driving their arguments forward. “We often talk about people being ‘T-shaped,’ ” says Hunter. “CDOs need to maintain their great depth in understanding design, but they also need to have the horizontal bar: to understand how corporations work at board level, have confidence and presence and command of facts and all the rest of it.”

For Dom Bailey, Strategic Director of brand design company Baxter and Bailey, design advocates will only be successful at the executive level if they’re given a certain amount of freedom – something he knows from experience.

Bailey was formerly Vice President of Brand and Communications at Yota, the Russian mobile phone company. While there, from 2009 to 2011, he rewrote his role to be more akin to a company-wide creative director, with specialists in product innovation, communications, PR and marketing reporting in to him.

Bailey helped scale Yota and bring on stream a suite of design-led products, but he’s wary as to the potential of executive administration wearing down board-level creative execs. “Sometimes it is hard to keep the flame alive,” says Bailey. “When you are at board level, 50 per cent of your time is spent aligning the company with the shareholders and board and not designing. That comes with the nature of the job and does get in the way. As you get drawn into the broader conversations around business strategy, then it’s harder to focus on the area you were brought in to address.”

In order to not get bogged down, Richard Whitehall, Partner at design and innovation consultancy Smart Design, believes design leaders must be wide ranging and fast moving. They should have the ability to make quick and accurate diagnostic assessments, to talk about design coherently with people from very different backgrounds and to look at things that are not seen as traditional design problems.

Whitehall points out that CDOs also need to be capable of knowing when to be ambitious and when to rein it in. “They need to recognise that there are different types of design problems and appreciate that not every question is necessarily a big strategic one. For example, a FMCG company may benefit from a very simple but effective change to packaging design on some of its lines. Understanding different tiers of problems is a very important quality.” CDOs must have the clarity of vision over what could bring big, evocative wins – and focus on those when they first come on board, to showcase to the company the power of design.

CDOs should pick areas first where design can bring a halo and create these good stories early on.

Richard Whitehall, Partner, SMART Design

He speculates that a CDO’s impact may have a short shelf life. “It’s going to be interesting to watch what the typical churn is for CDOs,” he says. “The question that interests me for the future is: how long can you be one before having to move on? Maybe the trick is not to fully integrate, and to preserve your distance. I do think that if you get too embedded, your value gets depreciated.”

Over at London's Canary Wharf, Clive Grinyer, Customer Experience Director at Barclays and an industry veteran, is having none of this: “It’s a two-year project to help someone understand the organisational culture and internal politics so they can really be effective. I don’t see people ‘going native’ – I see people understanding business issues and see them understanding customers.”

That’s exactly why companies like Barclays are beefing up their internal design teams. “It’s still very tempting for senior stakeholders to go overhead and omit some of the internal drudgery by contracting an external agency. They are brilliant at coming up with fresh ideas, but they struggle with implementing long-term change.”

On the whole Grinyer believes that senior-level executives understand the value of design; however, he still sees gaps, particularly in the operational and development sides. “Once projects get into build mode, then often decisions will be made for operational and developmental reasons rather than being based around the customer.” The psychological shift to factor in design as an everyday cost still hasn’t taken place in many businesses, according to Grinyer: “We still don’t spend enough. Business stakeholders understand that design is a good thing, but in my experience we’re not at the stage where they see it as an operational cost.”

Just as companies must evolve to incorporate design, designers must evolve to be effective in business. “The opportunity now is for designers to make design more integrated within businesses,” says Grinyer. “It’s to help the whole company be more creative. This may mean designers having to partially let go of their precious ‘We’re designers’ status, but maintain the ability to ensure everything is done for customer reasons and not just for operational reasons.”

For John V Willshire, Founder at innovation studio Smithery and former Chief Innovation Officer of media and communications agency PHD Media, creative leaders are especially valuable for established brands that have lost sight of their customers. “There are whole generations of people in businesses who are very adept at building on the work of their forebears, but when it comes to reappraising what the needs of the customer really are, they are lost.”

A CDO can spearhead the radically disruptive design-thinking that’s required for our world today. “Design was mistakenly thought to be about making things pretty, rather than making them work. Now that good businesses are looking again to reorientate themselves around their customers, they’re looking for a Chief Design Officer, rather than a Chief Marketing Officer,” he says.

“A great Chief Design Officer will have that gift of being able to look at whatever it is your business is doing as if…encountering that for the first time”, says Willshire, “and understand what will happen next in the market, rather than what the business wishes will happen.”

Willshire’s emphasis on the CDO’s ability to tune in to both the marketplace and the business and to intuit and catalyse solutions sounds almost magical. Perhaps it is: Apple cast a sufficiently powerful spell over customers worldwide to become, in 2014, the first company ever valued at more than $700 billion.

Successful design leaders seem to surf at the edge of the future and balance rationale and instinct: all the while tolerating the anxiety, ambiguity and uncertainty characteristic of operating in this liminal space between the known and the unknown, the old and the new, the past, the present and the future.

Why is this skill so extraordinary – the exception and not the rule?

In his book The Master and his Emissary, Iain McGilchrist makes the case that the Western world has become overly reliant on the quantitative or left hemisphere of the brain.

During a talk at the RSA in 2010, he said: “In our modern world we've developed something that looks awfully like the left hemisphere's world. The technical becomes important. Bureaucracy flourishes. And the need for control leads to a paranoia in society that we need to govern and control everything.”

If straddling the qualitative and the quantitative is the key to successful innovation in business, it seems CDOs and other board-level creatives have to swim against the tidal drift of wider culture.

McGilchrist, in his speech, draws on a quote often attributed to Albert Einstein: “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honours the servant but has forgotten the gift.”

The ascension of design-thinking in business is hopefully a sign that this will finally change.

Advice to board members looking to appoint a CDO

Be prepared to go outside your comfort zone

CDOs need to be able to enhance the board’s right-brain sensitivity so that they can ‘hear the music’. A great CDO can engineer moments that tune the board in to intuitive design-thinking.

Get ready for someone who can put your senior people into a different mode by reformatting the space, appealing directly to the senses using rich media, videos, music and even performance to catalyse these moments.

Taking leadership out of the office and putting them in contact with reality outside the boardroom will also do the job. For example, IDEO took senior execs from Proctor & Gamble on ‘service safaris’ to shops in Brixton and San Francisco, which helped them understand what diverse retail experiences might look and feel like.

– Mat Hunter, Chief Design Officer at the Design Council

Continue using external consultants, once in a while

The rise of big corporations building big design teams is a very wise move, but I don’t buy into the idea that it will always be the right answer. Everyone, however bright they are, hits their head against a brick wall sometimes. All businesses, however innovative, have this problem. There will always be a benefit to bringing in external mindsets and pulling together external experts to discuss a specific problem.

– Dom Bailey, Strategic Director of brand design company Baxter and Bailey

Be patient – change may take time

When companies view design as a catalyst to innovation, they do not judge design on aesthetics alone, but on value creation, problem solving, sustainability and process innovation as well. They will put their customers at the nucleus of a human-centred design approach. This might require reframing and restructuring the company, which can take years to implement.

– Hans Neubert, Chief Creative Officer at design and innovation consultancy Frog

What to look for: Five recruitment tips

1. Versatility

Employ a designer who has worked across a number of design disciplines.

2. Strategic mindset

Their track record should include designing systems, processes and experiences as well as objects.

3. Agency background

The senior talent pool of the design-led agencies is a great place to find candidates.

4. Cultural fit

Hire someone who will get along with the rest of the senior team.

5. A storyteller

Convincing the business that design has legs in a corporate world can require a lot of learning by doing – the CDO needs to be able to take people through meaningful and powerful experiences that change their perceptions.

– from Dr Kamil Michlewski, author of The Design Attitude and Senior Consultant at strategic brand consultancy The Value Engineers

Three tips: How to be a successful CDO

Align with the CEO and shareholders

It’s 50 per cent of the work. If you can achieve alignment on strategy, you stand a good chance of getting stuff done.

Be bold

Take brave decisions and don’t fear failure.

Embrace the brilliant misfit

One person can’t do it all. You need to hire a small team of brilliant thinkers and doers to make it.

– Dom Bailey, Strategic Director of brand design company Baxter and Bailey

Three attributes that make a great CDO

First and foremost, the role of a Chief Design Officer requires empathy, driven by curiosity to understand people beyond observation only.

In addition, the CDO must apply creative sensibility to the context of leadership to guide and inspire future thinking.

Lastly, great diplomacy and patience are necessary to navigate change across organisations that are often global and complex.

– Eric Quint, Chief Design Officer, 3M

Other articles in The Design Economy series:

- The Design Economy primer: how design is revolutionising health, business, cities and government

- Reinventing death for the twenty-first century

- Can design help shrink the ‘empathy deficit’?

- Can designers fix our ailing democracy?

- The ethics of digital design

- Is this the bank of the future?

- It’s education, stupid. Or, how the UK risks losing its global creative advantage

- Policy v5.127: Could government make services like Dyson makes vacuum cleaners?

- Will the Internet of Things set family life back 100 years?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Want to keep up with the latest from the Design Council?